After years of denial, Australians are embracing diesel-powered cars. But for some buyers, diesel may be a poor choice. Is diesel power right for you?

FOR DECADES, AUSTRALIAN CAR BUYERS resisted diesel power in their cars (although trucks have been predominantly diesel-powered for as long as anyone can remember).

Now, the pendulum seems to be swinging. Large European SUVs sold here are 80 percent powered by diesel, and more car models are also offering a diesel alternative. But in the rush to embrace this “new” technology, some buyers are making the decision based on wrong assumptions.

A petrol engine operates on a spark ignition while diesel engines use compression ignition to light the fuel. Air is drawn into the engine and subjected to high compression that heats it up. At peak temperature and pressure, the diesel fuel injected into the engine ignites as a result of the extreme temperature.

The advantages of diesel power are better fuel consumption, typically 25 to 30 percent better than a similarly performing petrol engine. Diesel fuel, despite huge investments in other forms of fuel, is one of the most energy efficient fuels available. With no spark plugs or distributors, diesel engines don’t need regular ignition tune ups. Because diesel engines must withstand higher compression ratios, they are built more ruggedly and usually travel greater distances than equivalent petrol engines before requiring major overhauls. Because of the way it burns fuel, a diesel engine produces far more torque, and this results in more flexibility and towing capacity. Modern diesel engines have overcome the earlier disadvantages of high noise levels and even the maintenance costs are being reduced.

So, it looks like a simple decision, right? Well, yes and no.

Diesel engines have had significant disadvantages that have kept them from achieving mainstream acceptance in passenger vehicles.

Because of the need for higher compression ratios, diesel engines must be built to withstand higher stresses and so they are heavier than comparable petrol engines. This also means diesel engines have traditionally been sold at a premium to a similarly equipped petrol model. Diesel engines operate at lower rpm and rely on high torque (Nm) rather than high horsepower (kW) so they tend to accelerate more slowly. Diesel engines require fuel injection and in the past this has been more expensive and less reliable than carburettors. Older diesel engines were harder to start in cold weather and used glow plugs that took time to warm up before you could start the engine. Diesel engines are often much noisier than petrol engines, vibrate more obviously and tend to sound clattery. And just for good measure, diesel engines often produce more smoke and smell funny.

Things are getting better.

But things are improving. We often test diesel-powered cars where the occupants and even those outside the vehicle would be hard-pressed to tell, from what they hear and see, that the power unit under the bonnet is diesel. The price differential between diesel and petrol power at the time of purchase is being reduced and service costs are becoming more similar.

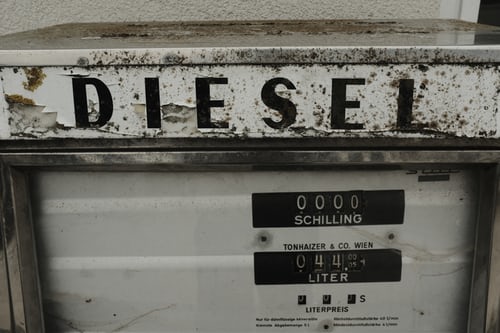

The ready availability of diesel at almost every service station also improves the practicality of diesel power, although many people are put off by the messy conditions around diesel pumps. (Diesel is an oily fuel so it can be messy to handle and leave a residue on the ground around the pump. Also, some four-wheel drive owners and truck drivers are willing to accept grubbier conditions than most passenger vehicle owners.)

On the other hand, the additional cost at the time of purchase plus the higher cost of diesel fuel and servicing mean, unless you clock up high mileages, it can take many years for the better fuel consumption will see you ahead financially. You should also take better resale into account – most diesel variants hold their value better than petrol models.

Wrong usage patterns can be expensive.

If you’re concerned about emissions, diesel engines are still “dirtier” than petrol engines and considerably behind hybrids. Particulates are tiny particles of soot that you often see spewing out of diesel tail pipes, especially if the particulate filter isn’t replaced regularly. And here’s a real issue for many people who buy diesel-powered cars. Diesel engines need to regularly reach an operating temperature sufficient to carry out particulate filter regeneration. The filter traps the soot from the exhaust and needs to be regularly emptied. The collected soot is burnt off at high temperature to leave only a tiny ash residue. This process can be either passive or active. Passive regeneration takes place automatically on motorway and freeway runs when the exhaust temperature is high. Because many cars don’t get this kind of use, manufacturers program the engine management computer to take control of the process. With active regeneration, when the soot loading in the filter reaches a set limit (usually about 45 percent), the ECU initiates post-combustion fuel injection to trigger regeneration. If the journey is a bit stop/start or you take your foot off the accelerator while regeneration is in process, the process may not be completed and a warning light will come on telling you that the filter is partially blocked. In most cases, there is only a relatively short time between the particulate filter being partially blocked and becoming so blocked it requires manual regeneration.

This is when things can become serious. If you ignore the warning light and continue driving in the same pattern, the soot loading will continue to accumulate until it reaches around 75 percent, at which time you can expect to see an array of other warning lights. At this point, driving the car at speed will not resolve the problem and you’ll need to visit your dealer for regeneration. Continue to ignore the warning signs and eventually the car will cease to operate properly and you will need a new (and expensive) particulate filter.

Unsuccessful regeneration results in extra fuel being injected that does not burn and drains into the sump. The fuel dilutes the oil, reducing the quality and raising the level. Diesel engines can run on excess engine oil, often to the point of self-destruction, so checking the oil level in a diesel engine is even more important than in a petrol engine.

The ash residue that remains in the filter even after successful regeneration cannot be removed and will eventually fill the filter. As we said, particulate filter replacement is not cheap. Most will last about 120,000 km or considerably longer under optimum conditions. Stop/start city driving is not an optimum condition and can lead to particulate filter replacement much earlier.

The most common form of particulate filter has an integrated oxidising catalytic converter located very close to the engine where exhaust cases will be hottest, for the most effective regeneration. Some models use a different filter which relies on a fuel additive (such as AdBlue) to lower the ignition temperature of the soot particles. This additive is stored in a separate tank next to the fuel tank and is automatically mixed with the fuel every time you refill. A litre of this additive should last around 2800 litres of fuel, or 40,000 km. This additive will be replenished at each service, at a cost. Eventually (at around 110,000km) you will need to have the additive tank refilled – a warning light will advise you when. Once again, it pays not to ignore this warning light – fuel consumption is likely to rise and regeneration may be unsuccessful to the point of requiring a new particulate filter.

Discuss your driving pattern with the dealer before deciding on diesel or petrol power. Most dealers will actively direct you away from the diesel option if they consider your driving pattern isn’t suitable. In any case, read the manual thoroughly so you understand what the various warning lights mean, and what action you should take.

Even diesel powered cars regularly used on motorways are showing signs of particulate filter systems failing to regenerate. Some have a very high top gear so engine revs may be too low to generate sufficient exhaust heat. In this case, occasional harder driving in lower gears should burn off the soot.

The regeneration will be initiated by the ECU every 500km or so, depending on vehicle use and will take five to 10 minutes to complete. You shouldn’t notice anything untoward, other than perhaps a puff of white smoke from the exhaust when the process is completed.

Some dodgy service centres are suggesting the solution to failed regeneration is removal of the particulate filter from the exhaust system, rather than having it repaired or replaced. This is illegal. A vehicle modified in such a way no longer complies with the air pollutant emissions standards it was designed to meet. Don’t be tempted.

The choice between diesel or petrol isn’t as simple as it seems. A few questions before you make the decision may save you from making an expensive mistake.

Hi just read that article 100% correct. I have just bought a 2018 triton last year and did a bit of research before buying it and found the Diesel engine has a lot of blow by which is common for these new engines in all makes of cars and light trucks. This blow by and exhaust gases from the egr valve make a sticky mess that can block up inlet manifolds and egr valves. The blow by can also block up your turbo intercooler.

Having pulled the breather hose off the rocker cover I saw it for myself. There is a product on the market called an oil catch can which catches the oil droplets in a filter from the blow by and lets the rest of the gases go into the engine. You drain the filter every couple of months it’s amazing how much it catches. This filter should prolong the life of your inlet manifold egr valve and intercooler . I have seen some light trucks same as mine that have done 30000km and there is signs of oil around the intercooler inlet and throttle body. There are kits available for a lot of makes and models but check with your service department before you go and fit one it may affect your warranty. I am very happy with mine I hope this helps.